The New World Order

by John Bennett

(C) 1991 by John Bennett. Published by The Smith, Brooklyn New York. Cover art by Jim Kay.

To Jesse Helms, without whose inspiration this collection might never have coalesced.

Contents

Piss Christ… 11

An Applicant Works Up His Brief Biography… 13

Torture & Confession… 16

What Have You Got to Lose?… 18

Picture This 19 The Manchurian Candidate & God Go Up the Hill… 20

Mr. Jones 22 Lexicon for Getting Along in the Modern World… 28

Reasons to Drink… 31

Morse Code… 32

Preparing for the Revolution… 33

Typhoid Mary of the Universe… 35

Fire… 37

Choosing… 38

Reading the Riot Act… 42

Crisis Line… 45

A Circuit Guru Does a Number on Dichotomies… 47

Doomsday… 49

Ru-Ru… 51

Gridlock… 65

Sex Dies… 67

Morbid… 68

Due to the Earthquake… 70

Molecular Conspiracy… 73

The New World Order… 75

Biography

What does one say for a bio? The years roll by, and I find I cannot come in from the cold. I find that I am less concerned, as time goes by, with what I am in opposition to than what it is what I have been in opposition to has kept me apart from. Of paramount importance for me in these days of wine and roses is to make an effort to lead my life minute by minute, blow by blow, in accordance with an inner voice and gyroscope that have next to nothing to do with the Industrial Revolution, the Information Age, and progress in general. I live alone with a white German shepherd named Sundance. I earn my keep through simple labor with my hands. I dance like a crazed dervish when the spirit moves me. I write, for the most part, what I seem compelled to write, and let the pieces fall. I am rapidly becoming what in my heart of hearts I always feared I’d become — an aging eccentric — and it ain’t half bad.

Ru-Ru

The way we make our poets. Inadvertently. In spite of ourselves. Over the years and through the eons. We catch them coming out the far side of polio with a hint of schizophrenia around the corners of the mouth, and then we place them in a nut farm at the age of twelve. Billy Joe, burly boy from Boise, heads the ward and shapes the action. “Hey there, yong thang,” he says, and cups the poet’s genitals. He does it with special gentleness, snake- eyes mesmerizing. “Roll over, yong thang,” Billy Joe says. “Time for ru-ru.”

***

White Smock comes dual-piping through the ward, his double-Windsor nestled in the pulse pool of his throat like a cobra head, crisp-crease pinstripes down below the smock hem, blocked over Italian imports. Stethoscope hanging from his neck like an earwig clinging to a head of cabbage, clipboard in hand. Consulting bed charts. Humming his way through, every now and then throwing a penetrating glance into the shock- wave eyes of an inmate. The whole ward tranked to the max for White Smock’s visit, every moan and twitch twenty leagues under the sea.

The Steinberg boy. So young to be so fucked. An unusual case. Bronchitis synapsing into pneumonia is one thing, but polio into schizophrenia is a first. There’s a paper in this. A new science. A gold mine. White Smock takes Jimmy Steinberg’s pulse. Billy Joe and his two assistants stand at the foot of the bed, watching.

“One-thousand-one,” White Smock murmurs. “One-thousand-two …”

The poet in Jimmy Steinberg can smell the street in White Smock’s clothing, smell the fresh California air. He can smell White Smock’s mistress, her armpits, her groin. His first off-ward contact in the three months he’s been there. He sends out the message to White Smock with his eyes: SOS! SOS! SOS! Jimmy Steinberg is a little man with a long white beard hanging on to a piece of wreckage in the middle of an ocean, waving at a plane flying overhead. He’s a naked albino in the snows of Killimanjaro, waving to a blind sherpa two ridges north. But eye contact isn’t cutting it with White Smock—send up the flares! Jimmy digs deep and brings up the words. He squeezes ru-ru between parched lips.

A whispered ru-ru isn’t ringing any bells either, so Jimmy lays on the emphasis: “RU-RU!” he roars, and with the strength of the insane gets a hold of White Smock’s tie just under the knot and yanks his face down close to his own so that their snot hangers are touching. “RU-RU! RU- RU! RU-RU!”

Jimmy goes off like a fire alarm, while inside his head the little editor with the green visor is blue-penciling like crazy. “No! No! No! SOS, you fool! SOS now, ru-ru later!”

Billy Joe cracks the poet’s fingers loose from the Windsor and the two assistants pull the doctor to safety.

Hypodermic ejaculating in the air. The plunge deep into the poet’s thigh. Pa-fummmmm, and he’s gone.

***

“Jimmy-Gee, Jimmy-Gee,” Billy Joe says. Jimmy Steinberg blinks and backs away. They’re in the rubber room, private and soundproof. It’s hard to tell where the door is.

Jimmy-Gee. Infectious. Endearing. Billy Joe’s pet name for the poet.

“You shouldn’t ought to have done that out there,” Billy Joe says. “That didn’t look so good for the ward. But Jesus! Did you see the look on old White Smock’s face?”

Billy Joe laughs, and Jimmy-Gee laughs too.

Then Billy Joe stops laughing. “Yes, well—that ain’t exactly what I call a show of gratitude,” he says. “Not exactly gratitude …”

Jimmy-Gee leans his head forward, cocks it to one side, waits.

“You know what’s coming?”

Jimmy-Gee shakes his head affirmative—time for ru-ru.

“But look here,” Billy Joe says. “I’m going to give you a choice. You done had a bunch of ru-ru. You want more ru-ru, or you want to be chastised?”

Jimmy-Gee blinks.

“You can have your ru-ru,” Billy Joe explains, “or you can get chastised. Ru-ru or a spanking.”

Jimmy-Gee clears his throat. He advances a preference. “Spa—spa-spank mah-mah-me pah-pah-please!

Billy Joe smiles at Jimmy-Gee like he’s just made a wise choice. Then he takes a common white sock out of his smock pocket. He takes out three bars of sink-size Ivory soap and puts them in the sock, pushes them down into the toe. He wraps the end of the sock around the fingers of his right hand and closes the hand into a fist.

“Okay, Jimmy-Gee,” he says, swinging the loaded sock. “Okay, my good man.”

***

Things Jimmy-Gee learned on the ward: you don’t walk fast and you don’t talk fast and you don’t make eye contact. You shuffle everywhere you go. You get right up when Billy Joe whacks the soles of your feet with his baton in the morning. And when someone goes off, you slide under your bed or move like a cat to a far corner and freeze.

Tommy the Giant used to go off at least once a week. Most of the time he’d just bash his head into the wall over and over again, setting off a chain reaction of head bashing, but one day after bashing his head five or six times Tommy pivoted and grabbed the man in the bed next to him and threw him across the room. Then he started moving through the ward like a tornado, smashing things, slamming people out of his way. It was genuine pandemonium. Jimmy-Gee did the cat crawl under his bed, and the one known as the Lynx moved with great speed without seeming to move at all straight into the bathroom.

The Lynx was 28 and had been under lock and key since the age of ten. Somewhere in there he spent three months in a sensory deprivation chamber, and when he came back out, they gave him paper and crayons to help make the transition back into the world. The Lynx set to work drawing exquisite landscapes, and then he began writing poems with end rhyme. The Lynx wrote in end rhyme and he spoke in end rhyme and the ward bathroom with the seatless white porcelain crappers was his hangout. He’d stand up against the wall and talk rhymes at you while you took a shit. He didn’t care how bad it stank, stink meant nothing to him. Jimmy used to go in there and sit on the porcelain rim just to listen to the Lynx talk. It was the Lynx got him writing poetry.

But this day the Lynx was in there all alone and Tommy the Giant was tearing the bars off the windows and it was Jimmy talking rhyme while lying under his bed with his eyes closed tight.

“Gawd, don’t make it hawd,” Jimmy kept repeating. “Gawd, don’t make it hawd.”

Billy Joe came through the ward door with his cattle prod and four orderlies. The orderlies took one look at Tommy the Giant peeling metal bars off windows and they pulled back. Each of them had a hypodermic with enough shit in it to sink a buffalo to its knees, but they didn’t have the stomach to go up against Tommy the Giant. Only Billy Joe went forward.

Jimmy opened his eyes and looked out from under the bed. Billy Joe was advancing down the ward, swinging his cattle prod. He was smiling and cooing. “Ah, Tommy, Tommy, Tommy,” he cooed. “Ah, sweet little Tommy.”

The ward went quiet. Tommy bent one more bar back, just to show Billy Joe (see that sucker? see what I have in me?), and Billy Joe kept advancing. When he got within ten feet of Tommy the Giant, he jabbed a man sitting on the floor with the cattle prod. The man let out a cry and wrapped his arms around his head. Billy Joe looked at the stricken man with wide eyes. Then he looked at Tommy the Giant.

“Gain!” Tommy said.

“Gain?” said Billy Joe.

“Gain!” said Tommy.

Billy Joe gave the man on the floor another jolt,

Tommy the Giant laughed and clapped his hands, and the Lynx peeked out of the bathroom.

“Gain?” said Billy Joe, and Tommy the Giant shook his head enthusiastically. Billy Joe fired off another jolt, and the man jerked around the floor.

Tommy the Giant got so excited he turned and began bashing his head against the wall again, making uh-uh-uh sounds with each collision. Billy Joe looked at the orderlies at the far end of the ward, and the bravest of them advanced. Billy Joe took the hypodermic from him and jammed the needle into Tommy the Giant’s butt, right through his pajamas. Tommy’s hands shot straight up in the air, splayed out against the wall, and then he slid to the floor. The orderlies dragged him away.

“The crude dude got rude,” the Lynx remarked as they passed the bathroom.

“That’s it, Lynx old buddy. That’s it in a nut shell,” Billy Joe said, and he stopped to pat Lynx on the shoulder and pinch his cheek.

***

They’re sitting in the cafeteria eating ice cream. Jimmy in his green robe, his mother in her street clothes, her hat on her head, her purse in her lap.

“The doctor says you’re coming along, dear,” his mother says. “He says you can come home soon if things keep going the way they’re going.”

Jimmy slides a spoon of ice cream past his lips and pushes it up against the roof of his mouth with his tongue. He likes the pain behind his eyes, spreading into his temples and then dissolving into a pleasant warmth. He smiles at his mother.

“It makes me so happy I could weep,” his mother says. “This past year you’ve been here has been the most upsetting year of my entire life.”

Jimmy scoops in more ice cream, keeps smiling.

“Too much smiling!” the little editor in his head says. “Let it come and go!”

Jimmy lets it go.

“Jimmy,” his mother says, and the way she says it he knows it’s going to be something bad. “Jimmy, how do you feel about Billy Joe?”

Uh-oh! SOS! Ru-ru!

Jimmy swallows the ice cream and wipes his lips with a paper napkin. “Why do you ask?” he says.

“Well,” his mother begins, and then she blurts it right out. “Billy Joe and I have been seeing each other.”

The smile comes back and locks in. He sees himself in his mother’s eyes. “May Day!” the little editor cries out. “May Day!”

“Oh dear!” his mother says, and her hand goes to her mouth.

“Blow this and you’re dead meat,” the editor says. “Bathrobes and slippers for the rest of your life.”

Jimmy clears his throat. He puts his hand over his mother’s. The smile limbers and his eyes go soft. “Ma, that’s great,” he says. “I couldn’t have got to where I am without Billy Joe.”

***

Jimmy’s in the back seat and his mother is up front. Billy Joe is driving. “One big happy family,” Billy Joe says, and winks at Jimmy in the rearview mirror.

They’re going home. They’re on the freeway heading south, weaving in and out of traffic at eighty miles an hour. Jimmy is thirteen and out in the world for the first time in over a year. Two years really, counting the polio. He’s a scrawny thing. He’s forgotten how to cry. His God is Ru-Ru.

He plans to slow poison his mother and Billy Joe. He wants to watch their teeth rot out. He wants to watch them vomit blood. He wants to wait until the last moment before scooping their eyes out with his thumbs. But his very first night in the house, lying awake in his old bed between crisp white sheets, he adopts another plan. He slips out of bed and dresses. Steals the mad money his mother hides in the collected works of Dickens. Releases the emergency brake and rolls the car out of the driveway. Starts the engine and drives down the block with the lights off. Turns the corner, turns on the lights, and turns on the radio. Lights a cigarette with the dash lighter. Drives south, toward San Diego.

It’s been two years since his father taught him to drive, but it all comes back—the driving, his father, the love. Jimmy pulverizes the love. His father is in a coffin of worms, and Jimmy is a thirteen-year-old car thief. He drives for an hour and leaves the car on a back street. Catches the 8:45 Greyhound to New York City.

***

The old man comes up to him every hour or two where he lies on the cot and puts an ear down close to Jimmy’s mouth. Then he puts the ear right down on his chest. After that he goes back over to the table and drinks coffee and smokes. Watches the sun come up, a golden wash over the mountain of city-dump garbage. The old man gets up and tosses some splintered crate wood into the wood- burning stove. A New Jersey winter. A squatter’s shack on the edge of Trenton. The old man picks up his guitar, an all-metal, self-made thing. He plays some blues.

Thirty-six hours later, Jimmy comes out of it. Even before his eyes open, one hand goes down to his knife in his boot. Both the knife and the boot are missing. Jimmy swings off the cot with both hands in a defensive posture. He and the old man stare at each other.

The old man pulls a little red wagon into town about once a week for supplies, and that’s when he first heard Jimmy doing his thing. Jimmy was standing on a corner reciting poetry, and every now and then he’d break into song. His voice was full of gravel. He was wearing Red Wing boots with flapping soles, filthy jeans, and a gray t-shirt. His arms were covered with crude tattoos, and there were tattoos on his face and the lobes of his ears. A straw hat lay upside-down at his feet, but he was in the wrong part of town to be hustling hand-outs.

While the old man watched from across the street, a middle-aged black woman came out of a shop, walked a straight line over to Jimmy, and placed a steaming bowl of grits at his feet. Then she walked a straight line back to her shop. Jimmy sat cross-legged on the icy pavement and scooped up the grits with his fingers. Then he got to his feet again, wiped his hands on his jeans, and sang praise to the woman who’d brought him the grits. He’d been on that corner for two days, sleeping on cardboard at night. The old man found Jimmy in a ditch a week later. He was unconscious in the tall weeds. The old man wrapped him in his top coat and got him into the red wagon—he weighed about as much as a feather. He pulled him on home.

The old man kept Jimmy Steinberg off drugs and alcohol for six months and taught him to play guitar. Jimmy put on weight and for the first time since the polio, got some color in his face.

“What that scar right across your throat?” the old man asked one day.

“Polio,” Jimmy said. “I had polio when I was a kid. The kind that hits the throat. It usually kills you fast. If it doesn’t, you’re pretty much good to go afterward. They had to cut a hole in my windpipe and stick a tube in there.”

“That’s the damnedest thing I ever heard,” the old man said. “How old you be anyway?”

“Seventeen,” Jimmy said. “Maybe eighteen. Right in there.”

***

Jimmy Steinberg is sitting in his room drinking coffee and staring out the window at the trucks backing up to the loading dock across the street. It’s a low-rent boarding house in the industrial south-end of Seattle, bathroom and shower down the hall. Mostly taxi drivers, stevedores and Nam vets. Every now and then one of the vets goes into heavy flashback mode and for a short time the second floor is just like the old days. Jimmy lays back on his bed smoking when this happens, listening to it all go down.

But right now he’s waiting for darkness and his gig. Lately he’s been leading off for heavy-metal bands. Mostly he just reads his rants and plays his guitar, but tonight he’s going to try something different.

He walks over to the shoe box on the table to see how his mouse is doing—he’s snuggled down in his rags, sleeping. Sleek, well-fed little bugger. No mouse ever had it so good. Jimmy strokes him with a tattooed finger. The mouse’s ears twitch, but its eyes don’t open. It’s just Jimmy-Gee, showing his love.

Jimmy pours another cup of coffee from the pot on the hot plate and rolls a cigarette. He lights the cigarette and goes down to check the mail. Usually he gets anywhere from five to ten letters a day, hardcore admirers, but today he sifts through the junk mail and comes up with a single letter, a square, pink envelope with three forwards and an L.A. return. He takes it upstairs and rolls another cigarette before opening it.

Dear Jimmy:

Imagine my surprise when Billy Joe showed me your picture in the Sunday paper! I didn’t recognize you! But Billy Joe did. He said he never reads that part of the paper, he just happened to open to it by accident, and there you were. I think that shows how much Billy Joe loved you and still does and how much you hurt him when you did what you did way back then, stealing the car and all. Anyway, let bygones be bygones, that’s what I always say.

Life has not been easy for me.I try to be a good wife to Billy Joe, but sometimes his work tortures him so that he—well, he’s not a cruel man, but his work makes him do things, and he’s always full of remorse after, and very tender. It’s just something I have to live with. Also, it’s hard for Billy Joe because of the age difference, and then with the cancer—I lost a breast and look way older than I am.

Anyway, on the bright side, I am becoming a writer! I go to a group every Tuesday and we read what we wrote to each other and give criticism. Here too I am older, and sometimes I feel “out of it” as the kids say. But last week I had my 60th birthday and I had a cake delivered to the group. They brought it in right when the group was criticizing my work, and it surprised them all! The man who delivered it lit the candles with a cigarette lighter, and then he led the group in singing Happy Birthday! They were so surprised that at first a lot of them didn’t sing, but finally they all joined in and for some reason I started crying like a baby and couldn’t stop. Brother!

Jimmy put the letter down without finishing it and stared out the window at the trucks backing up to the loading platform. He rolled another cigarette but didn’t light it. He left it lying on top of the letter. He went over to his mouse. Stroked it. Picked it up. Decided on a dress rehearsal. He held the mouse in his hand and talked to it while stroking its fur.

“Hey, little mousey,” he said. “Hey, little sleeker. Hey now,” he said.

He walked over to the window again with the mouse in his hand. He cleared his throat, and tilting his head back, slipped the mouse head-first into his mouth. He closed his mouth just enough to keep the mouse from backing out. He stood looking out the window while the mouse worked through its panic, nipping at his tongue and the insides of his cheeks. He felt the warm blood trickling down his throat. And then the mouse grew quiet.

“Good evening,” Jimmy said. “Tonight I’m going to offer you a different fare. Tonight I am going to recite the poetry of Robert Burns.”

It was working. He could talk around the mouse. He could enunciate. With a mike he’d reach the balcony.

“But first, first I am going to sing happy birthday to my one-breasted mother who just turned sixty.”

Jimmy closed his eyes, took in some air, and then opened his eyes again. The trucks down on the street came and went. The traffic roared along on the freeway up the hill. Helicopters flew over, and out in the hallway a door slammed and someone yelled, “Fuck you then, go shoot your veins full of shit, you sonofabitch!”

Jimmy began singing. “Happy birthday to you,” he sang. “Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday dear …happy birthday …” And that’s when the tears started.

“No, you idiot!” the editor in his head said. “Tears don’t cut it with an audience like this. You’ll blow it with tears. We’re talking hardcore here. We’re talking punk, heavy metal…”

And, as if in confirmation of what the editor was telling Jimmy, the mouse began to squirm and nip again.

Jimmy waited for the mouse to settle down and then resumed singing.

By the time he’d finished the birthday song the tears had dried, but the blood still ran hot and salty down his throat.

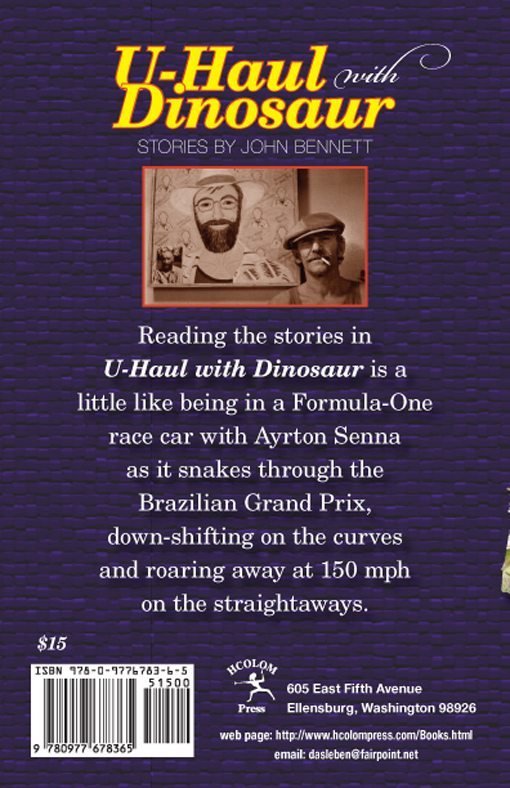

Ru-Ru was inspired by the early life of the poet Steven J. Bernstein. The story is also included in the short story collection U-Haul with Dinosaur. Click here to learn more…